It’s fair to say that Britain has been a cultural powerhouse when it comes to influencing tea drinking rituals of the western world.

Despite the recent renaissance of coffee in the UK, tea has been tightly woven into British culture at least since the mid-19th century.

It’s available in every corner shop and almost every place of work has a tea station. When kettles are not practical, there will be a thermos flask (invented by a Scot).

Inventor of the Thermos flask - James Dewar

Needless to say, it’s a subject that could fill a thesis but in this blog, we’ll try to cover the most important and interesting parts as we see it.

Go put the kettle on, fill your finest platinum jubilee teacup and dive into British tea rituals according to Chanui.

A brief history

Tea was introduced to Britain in the 17th century, primarily through trade with China. Initially considered a luxury item enjoyed by the aristocracy, tea gradually became more accessible to the general population as trade routes expanded.

As well as tea, porcelain and silk were very popular with British merchants. However, as the Chinese had little demand for British goods in return, Britain was forced to pay for imported goods with silver. This risked causing a silver shortage in Britain.

Britain’s solution was to begin smuggling opium into China to offset the trade deficit. This led to the Opium Wars in the mid-19th century, as China attempted to halt the opium trade, resulting in military conflicts between China and Britain, which ultimately led to China's defeat and the imposition of unequal treaties.

The Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841

Expansion

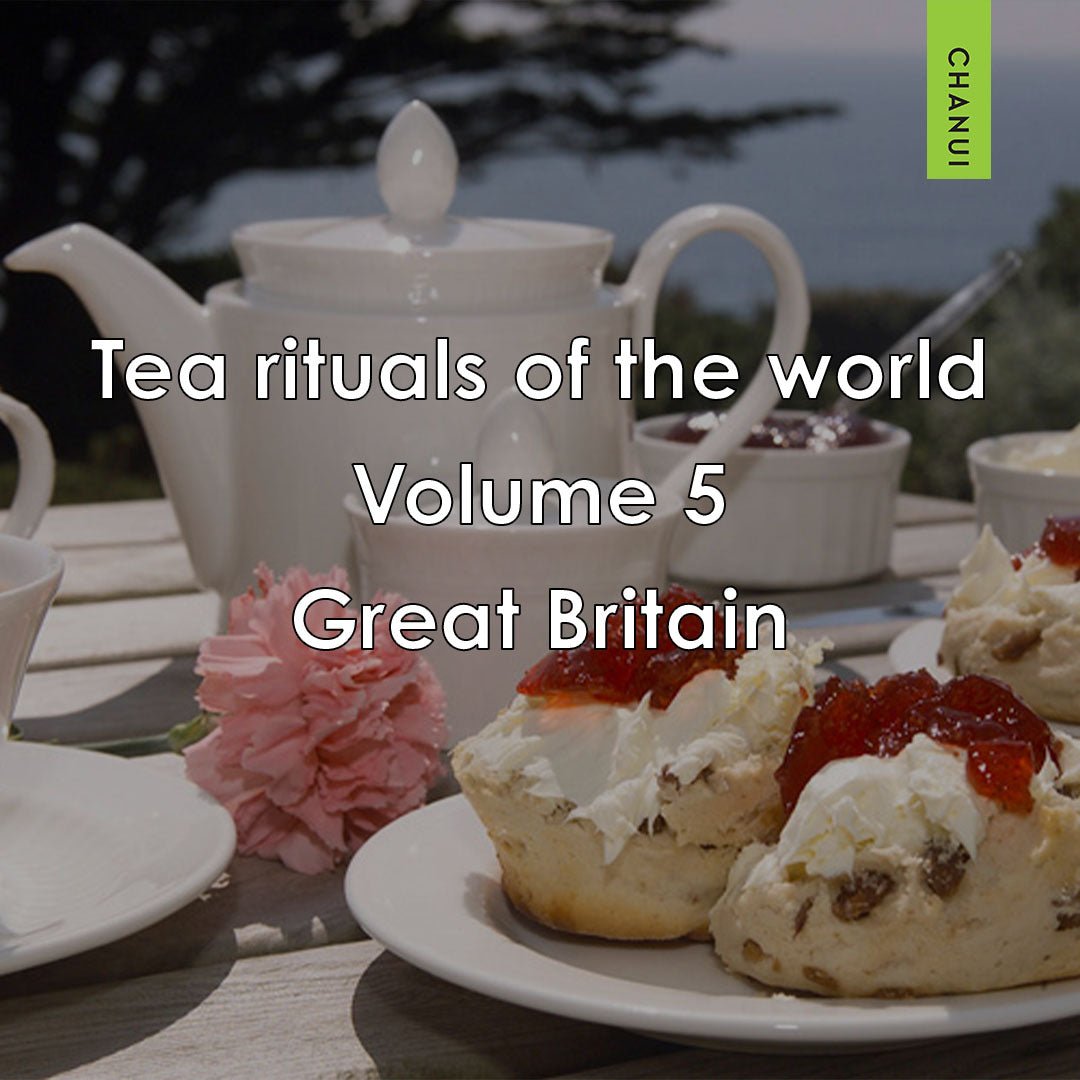

As tea became more widely traded by the British East India Company, Britain continued establishing control over tea-producing regions and exploiting their resources for economic gain.

Tea quickly became a symbol of the British Empire with tea rituals themselves becoming part of the process of cultural assimilation and domination. Plantations relying heavily on cheap labour continue to have a profound effect on both the geography and populations of ex-British colonies like Sri Lanka and India.

The British Empire's dominance in the tea trade had far-reaching effects on global commerce and cultural exchange. Tea became a staple beverage not only in Britain but also in colonies and territories around the world, influencing local cuisines, traditions, and social customs.

19th century advert for tea

High tea or low tea

Wider British culture is bound so closely to class structures where high = posh and low = common making this question a bit of a head scratcher.

But when you learn that it’s all about the height of the table they’re served at, it’s actually quite simple.

Low tea

Contrary to the name, low tea is actually posher than high tea, owing to the low tables from which it was traditionally served.

Low tea is synonymous with afternoon tea and gets its name from the tables it was traditionally served at - coffee tables. Afternoon tea was ‘invented’ by Anna Russell, Duchess of Bedford who ‘became despondent at the void between the two meals, and its consequent 'sinking feeling’.

She would ask for a light meal of sandwiches and cake to be brought to her room in the late afternoon and thus the ritual of afternoon tea was born.

Essentially, the hungry duchess got used to enjoying her afternoon meal of tea with dainty sandwiches and would invite her friends over to enjoy it.

With the rise of industry in the UK, evening meal times got later and later so the practice of having a meal between lunch and supper was quickly adopted.

High tea

Working women enjoying high tea

High tea is often misunderstood as an elite or aristocratic tradition, but its origins lie in the working class. The term "high tea" actually refers to the height of the table the meal is typically consumed, rather than its social status.

In Britain, particularly during the Industrial Revolution, workers in the factories and mines would return home in the early evening, hungry and tired after a long day's work. High tea was a substantial meal served at a higher, or "high," table around 5 or 6 p.m., providing a hearty repast to sustain them until dinner, which was often served much later in the evening. Of course, served with copious amounts of tea.

In contrast ‘afternoon tea’ is just another word for low tea.

Over time, the lines between high tea and afternoon tea have blurred, and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. The ‘high’ part was dropped and ‘tea’ usually refers to the evening meal enjoyed with or without the delicious brewed beverage.

There’s no exact line of where people use ’tea’ rather than ‘dinner’ or ‘supper’ for their evening meal but people in the north of England and Scotland more typically use ‘tea’.

Regional tea cultures

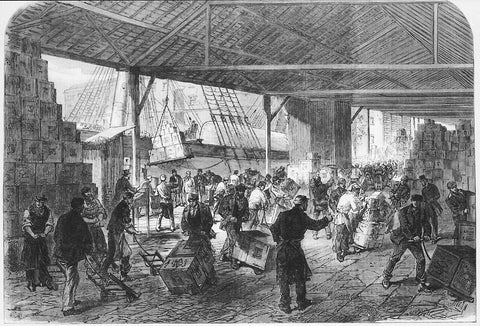

Scones, clotted cream and jam - two ways

Devonshire and Cornwall

Go to the highstreet of any self respecting city, town, village or hamlet in the South West of England and you’ll see a host of tea-shops offering cream tea.

Sandwiches, crumpets and cakes might vary but the one constant is the offering of ‘cream tea’ consisting of scones, jam and clotted cream. Or scones, clotted cream and jam depending on which side of the border of Devon and Cornwall you lie.

In Cornwall, jam goes first followed by clotted cream. In Devon, it’s cream first followed by jam.

This age old debate that divides two neighbouring counties so bitterly does the unexpected of actually unifying the rest of the British isles with everyone else agreeing that it doesn’t matter and the argument is stupid.

When do you add the milk?

Back when tea became popular in the aristocratic classes, low quality china cups were inclined to crack so people would add the milk first to temper the hot tea, protecting their crockery.

The finest china of the time was much stronger and so adding the milk last became a way to demonstrate that you had best china.

More to the point, adding milk last lets you more easily gauge how strong your eventual brew is.

Over the years there have been countless articles and fairly unrigorous studies on the subject with little actual data available that your writer could find.

Chanui’s position: Go with the wisdom of crowds and put your milk in last so you can more easily gauge the strength of the tea. Any perceived benefits will, over the course of a tea-drinking lifetime be negated by the inevitable countless cups of tea-flavoured milk.

Tea etiquette

For the vast majority of tea drinkers, enjoying a cuppa (see below) is a casual affair where avoiding rudeness consists of saying thank you and actually drinking what’s put in front of you.

But what happens if you’re invited to have tea at The Ritz for your teetotal mother-in-law’s 60th birthday party?

Don’t worry, we have you covered. Below is a list of dos and don’ts when it comes to enjoying afternoon tea in more convivial surroundings.

Holding the teacup: When holding a teacup, the proper etiquette is to use the thumb and index finger to grasp the handle delicately while supporting the bottom of the cup with the middle finger.

Regardless of what you have seen in lazy representations of British high culture, do not stick your little finger out as it is considered at best affectatious and gauche and at worst like you are taking the p*ss.

Sipping tea: Tea should be sipped quietly and gracefully. No slurping or going ‘aaaaaaaaah’. If you are wearing lipstick, try to sip from the same spot on the rim so you don't overly discolour the teacup.

Saucer usage: When not actively drinking tea, the teacup should be placed on the saucer rather than held in the hand. The saucer serves both as a resting place for the cup and as a catch for any drips or spills.

Stirring tea: When stirring tea, use a small spoon and stir gently in a circular motion to avoid clinking against the sides of the cup. After stirring, the spoon should be placed on the saucer, not left in the cup.

Napkin usage: A cloth napkin or serviette should be placed on the lap while enjoying tea. It's used for dabbing the lips discreetly and for blotting any spills or drips. Pretty standard stuff really.

Conversation and posture: During a tea event, engage in polite conversation and maintain proper posture. No slouching and talking about the most controversial topic in the news that day.

The bottom line is that tea is just an extension of British hospitality. Keep the shouting, slouching, slurping and swearing to a minimum and you should be fine.

Terminology

Brew: In British tea culture, "brew" is a widely used term referring to a cup of English breakfast tea. It's common to hear phrases like "put the kettle on for a brew" or "fancy a brew?" when offering someone a cup of tea.

Normal Tea: British tourist for English breakfast tea. Often heard uttered by confused British travellers unaware that many other countries do in fact drink a variety of different types of tea.

Builder's tea: This slang term refers to a strong, robust cup of tea typically favoured by construction workers and other manual labourers. Builder's tea is characterised by a generous amount of black tea, often brewed for an extended period so you can ‘stand the spoon up in it’ and served with milk and sugar. Popular choice with those needing a pick-me-up during a hard day's work.

Cuppa: "Cuppa" is a shortened form of "cup of tea" and is widely used in British colloquial language. “Make us a cuppa" is a common demand among friends and colleagues, signalling a desire to do something other than the task at hand.

Bernard Cribbings Right Said Fred is an excellent cultural text on this subject.

Rosy Lee: Cockney rhyming slang for ‘cup of tea’.

Tea leaf: Cockney rhyming slang for thief.

Final thoughts

British tea culture is a multifaceted tapestry woven with historical significance, regional variations, and surprisingly straightforward etiquette.

From its origins as a luxury imported item to its evolution into a staple beverage of the empire, tea has left an indelible mark on British society and the wider world.

Whether enjoying a refined afternoon tea or a hearty builder's brew, the rituals surrounding tea consumption reflect both tradition and adaptation.

So, whether you prefer a delicate earl grey or a robust builder's tea, the act of sharing a cuppa remains a timeless symbol of camaraderie and comfort in the UK.